It's been one year since I posted my first painted signs and mosaics. So happy anniversary to me! Over the past twelve months more than 200 painted signs from Britain, France, Germany plus a couple from Cuba, China and Laos, sixteen mosaics from Britain, Germany and Cuba, a few electric signs from the former GDR, and a couple of signs on glass have been published. With many more pictures up my sleeve there should be enough material to keep this blog going for quite some time. I hope you'll keep visiting.

To mark the beginning of the second year, let's have a sign about something I couldn't live without: books.

The opening of circulating libraries in Bath from the second half of the eighteenth century onward is closely linked to the growing popularity of the city's mineral water spas among the nobility and gentry. Taking the cure to improve one's health in the morning was followed by relaxation, social pleasures and cultural pursuit in the afternoon and evening, as Jane Austen described so wonderfully in

Northanger Abbey and in

Persuasion. Gentlemen and ladies would have wanted to read but few would have brought many heavy books with them, hence the need to be able to borrow some. Additionally by the end of the eighteenth century the price of books rocketed, making borrowing an attractive alternative to buying, especially in the case of less serious books such as novels, which were read primarily for enjoyment rather than study. For a fixed subscription, people could become members of a circulating library. These were usually founded by booksellers and binders who extended their business by lending extra copies of their books. It is estimated that by 1790 there were around six hundred libraries renting and lending books to fifty thousand people across England, and several of them were located in Bath.

The first circulating library in Bath was opened in 1728 on Terrace Walk by James Leake, a bookseller and printer originally from London. Although Leake's initiative proved popular, it was decried by Thomas Goulding, who described Leake's shop as "crowded by visitors carrying books" and argued in his 1728

Essay Against Too Much Reading that too much reading was undoing all the good of the mineral waters. Goulding wasn't the only one who despised circulating libraries but that didn't prevent people from joining them. Around 1740 William Frederick opened Bath's second circulating library at 18, The Grove. By the time of his death in 1776, Frederick was able to offer more than 10,000 books including 1,000 novels and romances, that were particularly popular with the ladies. Leake died in 1764 and his children sold his business to Lewis Bull, a jeweller, goldsmith and the keeper of a lodging-house. His son John took over in 1792 and kept the library going for a while but it seems to have disappeared by 1809. Meanwhile following Frederick's death, his circulating library was bought by John Sheldon and William Meyler, a magistrate and member of the common council. Another bookseller, William Taylor, of Church Street, began lending books too. By 1789 he had more than 7,000 books available at rates of 10s. 6d. per year, 4s. per quarter and 2s. 6d. per month. Bull's, Meyler's and Taylor's are amongst the seven circulating libraries listed in

The New Bath Directory for 1792. Yet there were certainly a couple more. For example, Samuel Hazard, of Cheap Street, who was in business between 1772 and 1806, is only listed as printer and bookseller, even if he also lent books at the same rates as Taylor per quarter and per year. It is estimated that by the turn of the nineteenth century there were at least ten circulating libraries in Bath. The most exclusive one was undoubtedly Marshall's at 23, Milsom Street, which opened in 1787. Originally it was jointly owned by Samuel Jackson Pratt and James Marshall, but by 1793 Marshall was the sole proprietor. The list of his subscribers read like a Who's Who:

two princes (the Prince of Wales and Frederick, Prince of Orange), five dukes, four duchesses, seven earls, fourteen countesses, many other nobles and forty-three knights. Professional customers were three admirals, four generals and many service officers down to twenty-six majors and seventy-one captains, and also ecclesiastics: one archbishop, six bishops and 114 clerics.

Phyllis May Hembry, The English spa, 1560-1815: a social history (1990, p. 150)

Marshall's library flourished between 1793 and 1799 but the rise in the price of books -up to 100%- was a serious threat to the business in general. Marshall increased his rates by 25% but ultimately even that didn't save him from being declared bankrupt in 1800 as the number of subscribers declined. His son joined him that year and together they managed to revive the library, stocking up to 25,000 books, until it was bought by Henry Godwin in 1808. Other circulating libraries in Bath combined to offer subscriptions at 5s. a quarter and 15s. a year to avoid closure. Still some circulating libraries may have suffered the same fate as Marshall and been bought by their competitors or new comers. Several names that would have been familiar by 1800 had disappeared by 1809 indeed.

Holden's Directory for that year lists only seven circulating libraries but more were certainly operating. The number went up to nine in 1819 according to

Gye's Bath Directory. Of these ones, only one exited before 1800: Meyler and Sons, who apparently had relocated from Orange Grove to Abbey Churchyard. Circulating libraries remained popular for several decades but little information about the ones from Bath is available for the post 1820 period.

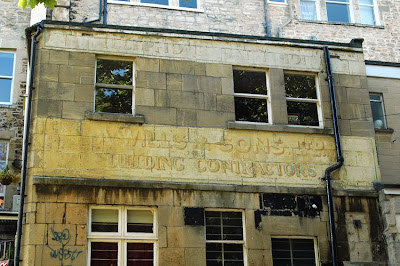

So, what about the circulating library that has left us this interesting sign at 43, Milsom Street?

Circulating Library

Circulating Library

And Reading Room

Bookseller

Binder

And

Stationer | | State

Lottery

Office |

One thing is sure about this sign: it was painted before 1826, the year the final draw of the state lottery took place.

During the period considered above, different sources mention several circulating libraries in Milsom Street:

- James Barrett (1792)

- William Bally, between 1768 and his death in 1774. His widow took charge of the library until it was purchased by Joseph Barratt in 1782. In 1794 William Bally's son, John, took it over and ran it until 1811, when he sold it to C. H. Duffield. This library was located at number 11 and then 12, until Duffield founded the Royal Union Library and Reading Rooms in Prince's Buildings. Between 1838 and 1840 this passed to Charles Archibald Bartlett

- Andrew Tennent, at number 24. His library opened in 1770 and was bought in 1780 by Charles Clinch and Samuel Jackson Pratt. It seems it was later purchased by Henry Godwin.

- the aforementioned James Marshall, later Henry Godwin, which was located at 23. That would be the wrong address, but Godwin published an advert in 1819, which read "Bookseller, Binder, and Stationer [...] State Lottery Office." Could Godwin have had a branch further down the street at number 43 ?

I was about to settle for that solution when one source mentioned that in 1822 one Frederick Joseph owned a bookshop and circulating library at 43, Milsom Street. His business was taken over by Eliza Williams in 1829. Apparently she remained there until 1868, when she moved to 19, Green Street. She kept her circulating library open until 1872 or 1873.

After that the premises at 43, Milsom Stret were occupied among others by the Bath and Counties Ladies' Club (in the 1860s and maybe for longer), a goldsmith (mentioned in 1876 and 1883), lace makers (1905 and 1907), the Royal Photographic Society (1980). Nowadays a fashion shop can be found on the ground floor while the upper floors are occupied by the Italian restaurant of a TV chef.

Finally, to conclude today's post, there are a couple of historic pictures of Milsom Street on which it is possible to catch a glimpse of the painted sign above. On the first one taken in the

1920s, the sign is on the second house from the right (windows two to four). On the view taken in

1981, it is to the right of the four columns supporting the pediment. Notice how dark the façade of the former Circulating Library was. Fortunately the sign was preserved when it was cleaned.

Location: Milsom Street, Bath, Somerset / Picture taken on: 17/07/2010

.jpg)